The origin of the Alexander Technique

ALEXANDER TECHNIQUE

Felipe Bojórquez Espinosa

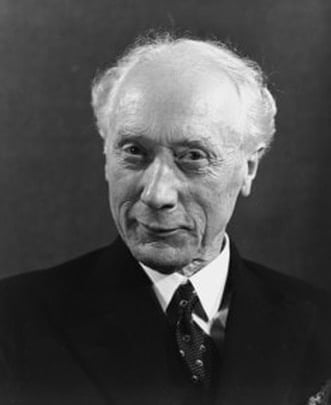

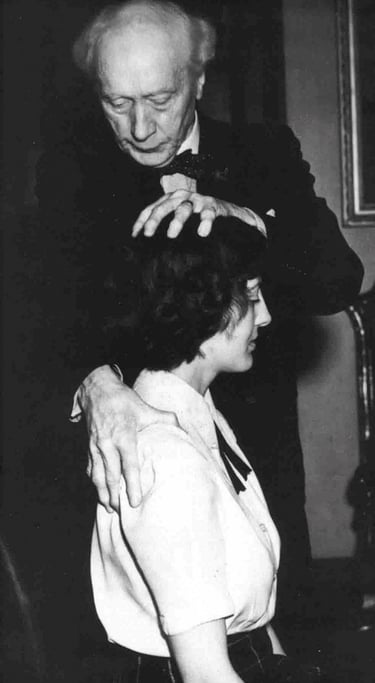

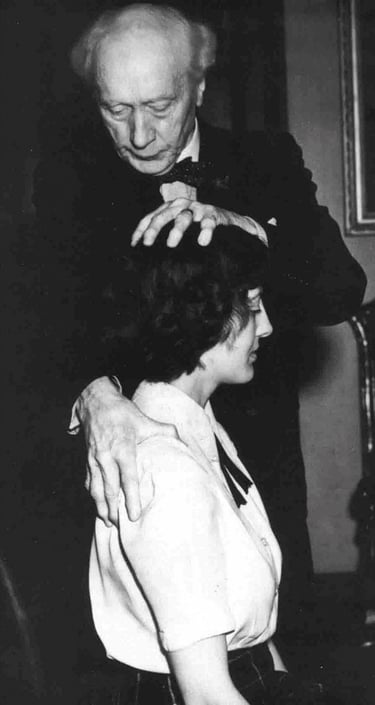

Frederick Matthias Alexander (1869 – 1955)

Frederick Matthias Alexander was the eldest of eight siblings, born in Wynyard, on the northwest coast of Tasmania, Australia.

From a very young age, he experienced health issues related to his respiratory system. As a young man, he faced a serious problem that interfered with his career as an actor: he tended to lose his voice during public performances. The doctors he consulted were unable to help him, so he decided to investigate on his own to understand what he was doing that caused him to lose his voice.

Through this exploration, Alexander made discoveries that not only helped him solve his vocal difficulties but also revealed principles useful in many aspects of daily life. These insights became the foundation of what we now know as the Alexander Technique.

Anyone can relate to the development of Frederick Matthias Alexander’s story, and to some extent, we can all follow the path he took.

Alexander showed great potential as an actor, but his vocal problems reached a critical point in his early twenties, just as his career was taking off. Despite taking acting and elocution lessons from prominent teachers, he began experiencing hoarseness during performances and consulted a doctor. The doctor examined him, found no pathology, and assured him that he had simply overused his voice, advising him to rest. Although Alexander’s voice seemed fine at the start of his next performance, the problems quickly returned, and by the end of the show, he could barely speak. He felt deeply anxious about the future of his career.

He reflected on his situation and reasoned that he must be doing something in his performance that was straining his voice—something he did not do at other times. He returned to the doctor for professional guidance and asked to be observed while speaking and reciting, hoping to identify the cause. The doctor said something very telling: “I cannot see the problem.” Alexander realized that he was creating his own vocal problem by doing something that seemed normal, even to a medical expert. The doctor admitted that he could offer no further help.

Determined to solve the issue, Alexander returned home to experiment through self-observation. At first, like the doctor, he saw nothing unusual. With practice, he began noticing small actions, such as pressing his feet into the floor. Over time, he realized he had a tendency to tighten the muscles at the back of his neck while reciting—a reaction to stressful or fearful situations, also known as part of the “startle pattern.”

It took some time before he discovered how to avoid unnecessary neck tension. When he managed to release this habit, his voice became less strained and his breathing more free. He had uncovered the first piece of the puzzle of his Alexander Technique: the Primary Control.

The way the head relates to the spine affects overall coordination, but at that time, Alexander was observing the specific effect on his vocal mechanism. As he continued working in this way, his voice became more reliable, and he clearly saw that the way he used his body influenced its functioning. This realization became central to his thinking and one of his key principles: “Use Affects Function.”

As Alexander attempted to avoid several of the habits he had observed, he realized that the situation was more complex than he initially thought. He noticed that reorganizing his head made him feel lighter and more energized. However, when he became deeply engaged in his recitation, he would revert to old habits, which now included lifting his chest and narrowing his back, restricting his breathing and putting pressure on his larynx. This insight crystallized into another key principle: Psychophysical Unity —the mind, body, and emotions are interdependent entities functioning as an indivisible whole.

He now needed to find a way to prevent his head from falling back and down, allowing his back to lengthen and widen and his larynx to remain balanced and flexible, even when fully absorbed in any activity.

Alexander observed that the body did not function in isolated sections but as a complete mind-body unit. He realized that focusing on small parts of the body, such as only the vocal organs, was ineffective. His new approach became far more effective when he considered the Whole Self, integrating mind, body, and emotions.

Sometimes, to his surprise, Alexander noticed (while observing himself in mirrors) that he was not doing what he felt he was doing. This was a highly significant discovery and became an essential part of his understanding of his vocal problem. By then, he had observed that the same tension pattern appeared in his everyday speech as in his acting voice. He realized he could not rely on sensory feedback from his nervous system to tell him what he was actually doing. This insight became another key principle of the Alexander Technique, known as Faulty Sensory Appreciation. (Everyone has the potential for unreliable sensory perception, even in simple situations, like thinking we are hearing a unison when it is actually an octave.)

Looking in the mirror, Alexander understood that merely intending to do something new was not enough to create effective change because his old habits were stronger than his new intention. He realized he needed to be extremely specific about which muscular patterns to stop. This became a cornerstone of his technique, which he called Inhibition. He discovered that stopping the old pattern had to be a continuous priority until the old habit weakened enough for the new pattern to be available without interference. By practicing Inhibition, he began to achieve significant progress.

This realization—that sheer determination or forceful effort to act differently was ineffective—led him to consider the influence of emotional state and attitude toward speech. He saw that while he could not always choose his emotional state, he could choose his thinking, which had a profound effect on both emotions and coordination. This insight evolved into the concept of End-Gaining, the habit of trying to achieve a goal at all costs. His alternative strategy was to focus on the best means, which would eventually lead him to the intended outcome.

Alexander also discovered a way to accelerate the process of change, a concept he called Direction. He realized that trying to place the head “in the right position” directly was ineffective. Instead, he needed to access the innate reflex within us that allows direction to happen naturally. This ability to self-direct is something we are born with but often lose as we grow and adopt habits imposed by external instruction. He found that by guiding the movement or release of a specific part of the body, with the intention for it to occur, the subtle influence of intention could accelerate the change.

By combining Inhibition and Direction, Alexander now had two powerful allies working against his destructive habits.

Alexander realized it was important not to force change through effort, which he described as the negative approach of “Doing”. Instead, he used Inhibition and Direction to allow his head to balance naturally, referring to this new approach as “Non-Doing”. He was allowing changes to occur rather than forcing them. He discovered that this worked at a very subtle, reflexive level. By guiding himself throughout his activities, his coordination and breathing improved, his sensory awareness became more reliable, his movements were filled with balance and lightness, and his performances were admired. He became well-known for his resonant voice.

His journey also included self-acceptance as a crucial part of personal development. He had to recognize deeply ingrained habits and approach change with patience and perseverance.

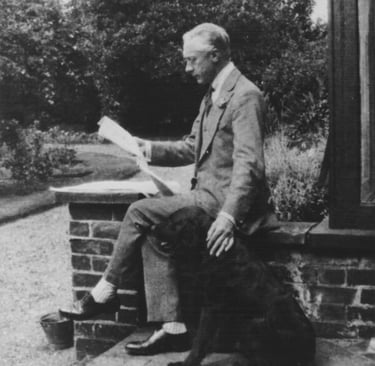

Alexander’s fame, both as an actor and teacher, continued to grow, and by 1895 he was running a thriving practice in Melbourne. Initially, his students came primarily from the dramatic arts. However, when local doctors learned of his work, they began referring patients to him, and soon the number of medical clients surpassed those from the theatre world.

In 1899, Frederick Matthias Alexander moved to Sydney. His reputation had preceded him, and he was soon inundated with work. Although the medical community generally held some reservations about his method, the renowned surgeon J. W. Steward McKay was convinced of its value and suggested that Alexander move to London to gain the recognition his work deserved.

Alexander embarked for London in April 1904, after a farewell tour during which he performed Hamlet and The Merchant of Venice with a company composed almost entirely of students who had come to him through medical referrals.

In London, his practice grew rapidly, and he soon became known as the “protector of London theatre.” Many of the most celebrated actors and actresses of the time took lessons with him. As his work gained wider recognition, Alexander faced those attempting to imitate him. To preempt potential plagiarism, in 1910 he published his first book, “The Supreme Inheritance of Man”, which he described as addressing “the great stage in human development in which man moves from subconscious to conscious control of mind and body.” The book was very well received and continued to be republished throughout Alexander’s life.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 caused an immediate decline in the number of Alexander’s students. Knowing that he would lose the skills and understanding he had painstakingly developed if he stopped teaching, Frederick Matthias Alexander decided to move to the United States to continue his work. For the next ten years, he divided his time between the U.S. and Great Britain, spending half a year in each country and hiring an assistant on each side of the Atlantic to meet the growing demand for lessons.

Between the two world wars, Alexander’s work gained increasing recognition and influence. In addition to his numerous students, he counted prominent supporters such as William Temple, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Sir Stafford Cripps, Esther Lawrence of the Froebel Institute, George Bernard Shaw, and Aldous Huxley.

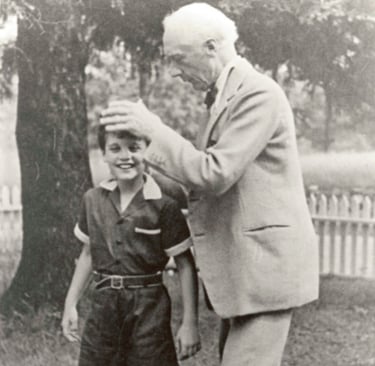

In 1923, he published his second book, “The Use of the Self”, with a foreword by John Dewey, the American educational philosopher, who became one of the most ardent and consistent advocates of the Alexander Technique. Dewey wrote that Alexander’s work contained “the promise and potential of the new direction necessary in all education.” Like Dewey, Alexander believed that education was key to social evolution. In 1924, he founded the first school based on his principles at his London studio.

Directed by Irene Tasker, a teacher who had worked with Maria Montessori, the school welcomed children aged three to eight. Although it followed a standard curriculum, its primary focus was teaching children to develop the “Use of the Self.” After ten years, Tasker emigrated to South Africa, and under the leadership of Margaret Goldie, the school relocated to the countryside. In 1940, due to World War II, the school was evacuated to the United States, and attempts to reestablish it in England after the war were unsuccessful.

For many years, Alexander had been encouraged to establish a formal teacher training system for his technique. Initially, he hesitated, wanting first to ensure there was sufficient demand for his work and, most importantly, that he could train teachers to the highest standard.

In his view, anyone intending to teach the Alexander Technique needed to be prepared to apply its principles and procedures to their own Use in everyday activities before attempting to teach others to do the same.

His third book, “The Use of the Self”, was published in 1932, in which Frederick Matthias Alexander aimed to describe the process through which he had developed the Alexander Technique. Nine years later, he released his final work, “The Universal Constant in Living”, a series of articles on the concept of Use, in which Alexander particularly emphasized the harmful effects of exercise systems and “physical education” programs that ignored the unity of mind and body.

Shortly after the end of World War II, his supporters in South Africa attempted to replace the existing physical education methods with a system based on Alexander’s ideas. This provoked an attack against him and his work by Dr. Ernst Jokl, director of the South African Physical Education Committee.

During a heated legal battle that lasted four years, Alexander faced opposition from many members of the medical profession. However, two highly influential figures testified in favor of the scientific validity of his work: Sir Charles Sherrington, a Nobel Prize–winning neurophysiologist, and Professor Raymond Dart, the renowned Australian anatomist and anthropologist.

Alexander ultimately won the case in 1948, although a serious stroke had paralyzed the left side of his body, preventing him from attending the trial. During his recovery, he applied the very principles he had discovered. In his old age, deprived of nearly all his physical strength, he had to rely more than ever on the power of pure instruction. His students later testified that he never taught better than during the five years preceding his death.

During these years, Frederick Matthias Alexander continued refining his method while maintaining his private practice and supervising the work of the teachers who assisted him. He passed away on October 10, 1955, after a brief illness.

Alexander’s achievement was immense. On his own, he developed a simple, practical, and innovative method for studying and resolving a specific problem, establishing a revolutionary way of understanding human functioning.

It can certainly be said that Alexander is one of the most underestimated thinkers of the 20th century. This can be explained for two main reasons: one relates to Alexander’s own character, and the other to the skepticism of medical and educational institutions.

He gained a clear understanding of some fundamental truths about what it means to be human and discovered that the root of our problems does not lie in what happens to us, but in how we react to it. He developed a way to help us choose how we respond to life’s events consciously rather than automatically, a core principle of the Alexander Technique.

The Alexander Technique helps us develop the ability to be present, creative, and spontaneous, rather than living, practicing, or performing in a “predetermined” way based on preconceived ideas of what is “correct.”

It encourages deep observation of our reactions, helps us face our fears, and promotes flexibility of thought and movement—integrating mind and body. The method empowers us to choose how we respond to the stimuli of everyday life, and it is in this conscious choice that our true freedom lies.

Related articles

Well-balanced flutist

Alexander Technique and Mindfulness in everyday musical practice.

Specialized support for high-performance flutists and flute students.

© 2025. All rights reserved. Privacy policy.

Menu:

Lessons

About me